Autistic Masking

I was diagnosed with autism when I was 16. Like many autistic people (though not all), I grew up masking my autism. Doing my best to suppress parts of me I recognised seemed different to other people, parts I grew to be ashamed of as things happened which taught me I should be. I didn’t know that what I was doing was called masking. I didn’t know that other people didn’t do it to the same extent that I did. I also didn’t really know that I was doing it.

I want to start this blog post by saying that although masking has been hugely detrimental to my mental health at times, it has also allowed me to do a job I love, make friends growing up, and ‘blend in’ when I have wanted or needed to. Hence, I believe the conversation around masking is more nuanced than it can sometimes seem. Whilst it can cause harm, it can also be a privilege to be able to mask at times. I don’t want to stop masking completely, even if I thought I could. Everyone will feel differently about this, but that’s where I’m at right now in my life!

What is Autistic Masking?

Autistic masking refers to how some autistic people adapt their behaviour to try to appear neurotypical. This can be an unconscious or conscious process.

It involves autistic people attempting to suppress their instinctive autistic traits, observing those around them to copy how they behave and react to things, and then mimicking this to not stand out.

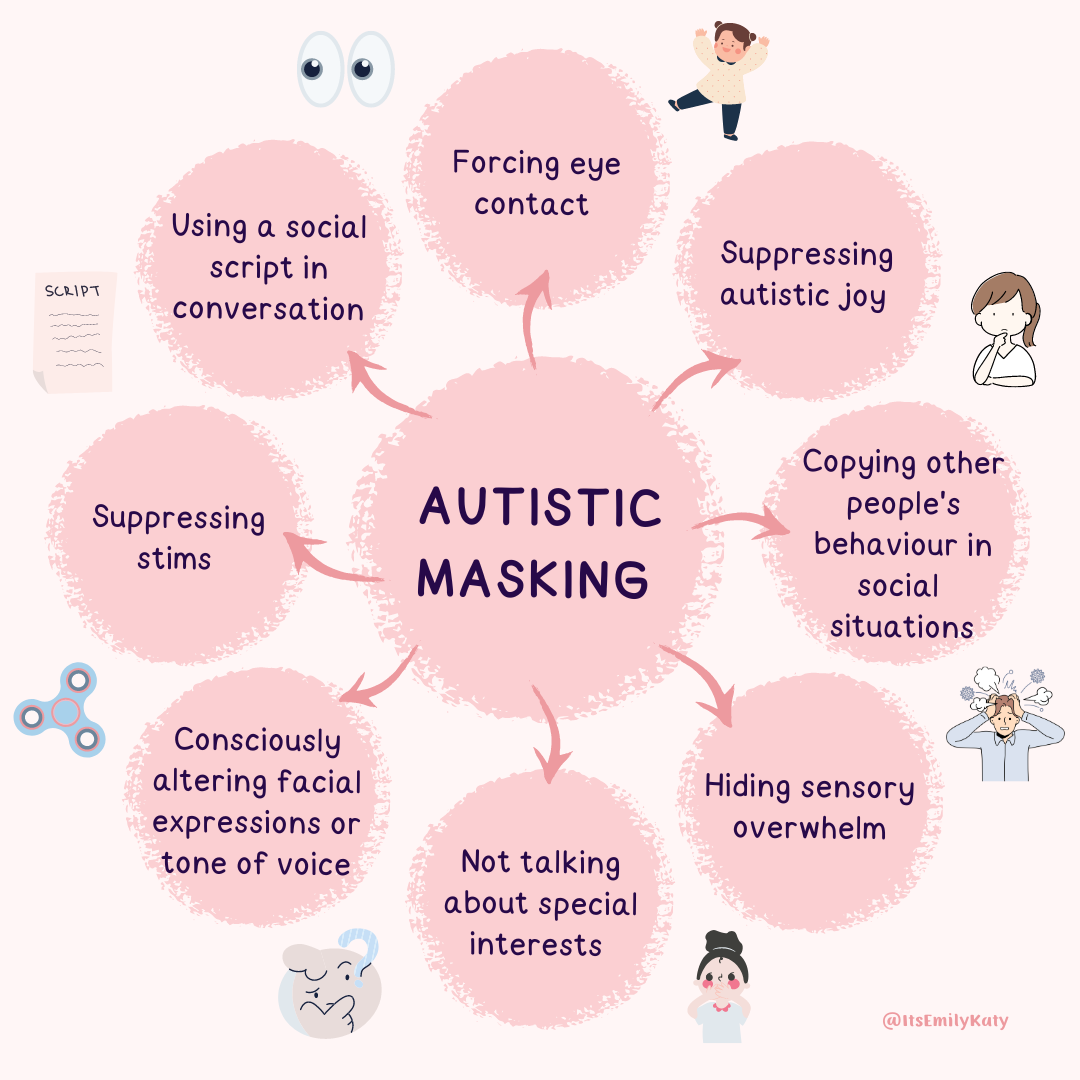

Examples of Autistic Masking

forcing yourself to make eye contact

suppressing stims

consciously adapting facial expressions

trying to control the tone of your voice

learning a script for social situations

copying those around you to know how to act

suppressing authentic reactions

withstanding painful sensory experiences

not sharing own feelings or interests

Effects of Autistic Masking

A variety of research has investigated the effects of autistic masking, finding the following:

It is found to be a risk marker for suicidality (Cassidy et al., 2018).

High masking is linked with mental health difficulties such as anxiety and depression (Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019).

It contributes to autistic burnout (Raymaker et al., 2020).

The National Autistic Society highlight that:

Masking may contribute to low self-esteem, feelings of disconnection, and ‘people pleasing’ tendencies, which can increase vulnerability.

It may increase safety for some autistic people, for example reducing bullying, stigma and abuse.

Some autistic people report benefits of being able to work and make friends.

As I describe in Girl Unmasked, for some autistic people, masking occurs due to a physical presence of risk. It may not be safe for them to be their true authentic autistic self. This is especially true for Black autistic people, for whom not masking can carry an even greater risk (Abrams, 2020; Ventour-Griffiths, 2022).

“Research has repeatedly shown that keeping our true selves locked away is emotionally and physically devastating. Conforming to neurotypical standards can earn us tentative acceptance, but it comes at a heavy cost. Masking is an exhausting performance that contributes to physical exhaustion, psychological burnout, depression, anxiety and even suicidal ideation. Masking also obscures the fact that the world is massively inaccessible to us.”

The CAT-Q

The Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire is a self-report questionnaire measuring camouflaging, compensation (strategies to compensate for difficulties), masking (strategies to hide autistic traits) and assimilation (strategies to try to fit in with others) in adults. A total score of 100 or above suggests camouflaging of autistic traits. You can take the questionnaire here.

Interestingly, the data from the CAT-Q suggests that generally, autistic women and non-binary people camouflage/mask the most, but neurotypical women camouflage less than neurotypical men. Autistic males are found to not camouflage much more than non-autistic men. Obviously this is generally, so there will be high masking autistic men and low masking autistic women. There is also not much difference in masking levels between autistic and non-autistic non-binary people, as their level of camouflaging is much higher in general, irrespective of if they are autistic or not.

Things to remember

Not every autistic person masks

Masking can be important for some autistic people’s safety

Masking can also have devastating consequences

Often masking is an unconscious process

‘Unmasking’ is not an easy process

You do not have to completely unmask and there is no pressure to unmask

If you don’t already, one day you will love yourself just as you are <3

GIRL UNMASKED (The Sunday Times Bestseller) is available to order from Amazon and all major bookstores! Available as a hardback, eBook and audiobook. https://linktr.ee/girlunmasked

References

Abrams, A. (2020). Black, disabled and at risk: the overlooked problem of police violence against Americans with disabilities. https://time.com/5857438/police-violence-black-disabled/

Cage, E. & Troxell-Whitman, Z. (2019). Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(5), 1899-1911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-03878-x

Cassidy et al. (2018). Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Molecular Autism, 9(42). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-018-0226-4

Engelbrecht, N. (2020). The CAT-Q. Embrace Autism. https://embrace-autism.com/cat-q/

Hull et al. (2018). Development and validation of the camouflaging autistic traits questionnaire (CAT-Q). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 819-833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3792-6

Miller et al. (2021). “Masking is life”: experiences of masking in autistic and nonautistic adults. Autism Adulthood, 3(4), 330-338. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0083

National Autistic Society. (undated). Masking. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/behaviour/masking

Raymaker et al. (2020). “Having all of your internal resources exhausted beyond measure and being left with no clean-up crew”: defining autistic burnout. Autism Adulthood, 2(2), 132-143. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2019.0079

Ventour-Griffiths, T. (2022). Autistic while Black in the UK: masking, codeswitching, and other (non)fictions. NeuroClastic. https://neuroclastic.com/long-read-autistic-while-black-in-the-uk-masking-codeswitching-and-other-nonfictions/