Challenges for Autistic University Students

Autistic students are more likely to drop out of university or take time out of their course than any other group (North East Autism Society, 2023).

36% of autistic students who enrolled on an undergraduate degree in 2019 did not complete their degree after three years, compared to 29% of the general population (North East Autism Society, 2023). It is worth remembering that this was during COVID, when distance learning may have been easier for autistic students (it certainly was for me!). Figures from prior to COVID suggest higher drop-out rates of over 60%, with Gurbuz et al. (2019) stating that less than 40% complete their studies.

56% of autistic students have considered dropping out of university, compared to 15.3% of non-autistic students, according to one study (Gurbuz et al., 2019).

Autistic students are the least likely to graduate with a 1st or a 2.1 out of any disability group, according to the Office for Students (OFS).

These statistics are all very sad. I started my university degree in 2019, and until COVID hit in March 2020, I was definitely toying with the idea of dropping out. I didn’t even move into halls, I stayed at home, yet I would return home after a day at university and meltdown.

Reasons for these statistics:

The North East Autism Society reported that only 21% of autistic students who responded to a survey by Disabled Students UK received the support they needed at university. They experience higher rates of burnout and mental health challenges, contributing to them being more likely to consider dropping out (Cage & McManemy, 2022).

Other reasons include:

Universities lacking understanding of autism

Higher rates of mental health difficulties amongst autistic students

Autistic students not feeling part of a group or accepted

Finding the change of university difficult

Not receiving adequate support

(Cage & Howes, 2020)

Health Education England state that without appropriate adjustments and support, not only do autistic students’ education suffer, but so does their health and well-being (Griffin & Pollak, 2009; Young et al. 2021). And this is understandable, because it is not sustainable to push through the stress and overwhelm university can cause forever.

Under the Equality Act 2010, reasonable adjustments legally have to be made. However, because these are unclear and differ between students, they are often not applied (Craig, 2018) and students can feel like they have to “muddle through” (King, 2018).

Possible reasonable adjustments:

Provide recordings of lectures due to information processing challenges

Provide copies of powerpoint slides in advance to enable student to know what to expect

Provide clear, concise written instructions and enable clarification to be sought when needed

Provide advance notice of any changes where possible

Allow supports to help with concentration or sensory needs in lectures e.g. doodling, fidget toys, headphones

Regular breaks during lectures

More frequent check-ins or communication with personal tutor, including where student does not have to initiate approach

Avoid ambiguity where possible

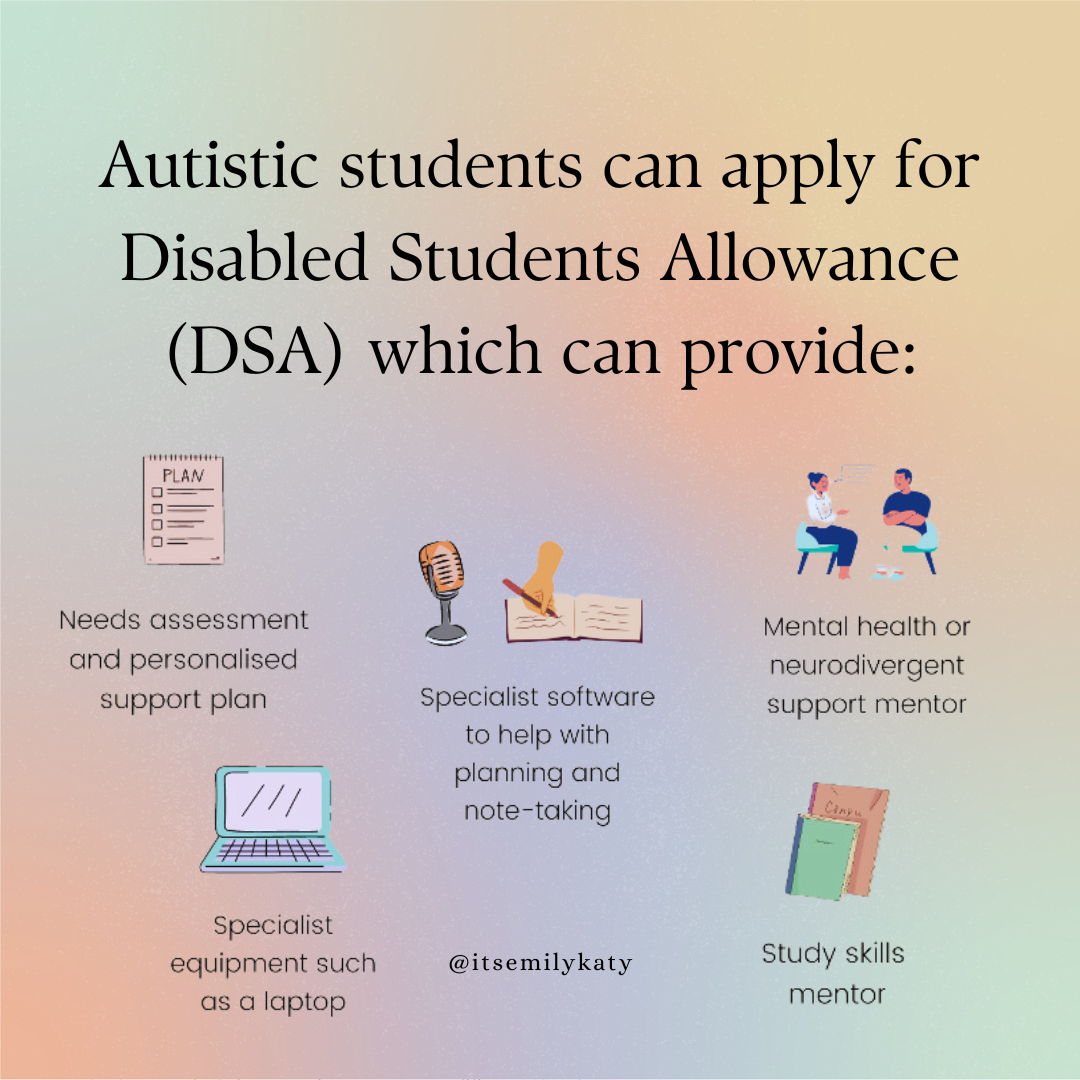

Autistic students can apply for Disabled Students’ Allowance (DSA) which can provide:

A needs assessment and personalised support plan

Specialist software to help with planning and note-taking

Specialist equipment such as a laptop or recording device

Mental health or neurodivergent support mentor

Study skills mentor

I found DSA really helpful, and I know so many others for whom DSA has enabled them to manage at university, and even be able to enjoy their experience.

Things are getting better. Understanding is improving. There are many autistic people who love their university experience, so please don’t be put off if you’re an autistic person looking to go to university. Just know the support you are entitled to and the attitudes you do not have to put up with. Remember, you are allowed to fight for yourself and you deserve to have your needs met.

References:

Cage, E. & Howes, J. (2020). Dropping out and moving on: a qualitative study of autistic people’s experiences of university. Autism, 24(7), 1664-1675. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320918750

Cage, E. & McManemy, E. (2022). Burnt out and dropping out: a comparison of the experiences of autistic and non-autistic students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 792945. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.792945

Craig, A. M. (2018). An exploration of the concept of reasonable adjustments in pre-registration nursing education in Scotland. Ph.D. Thesis. The University of Manchester. Retrieved from https://research.manchester.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/an-exploration-of-the-concept-of-reasonable-adjustments-in-pre-re

Griffin, E. & Pollak. D. (2009). Student experiences of neurodiversity in higher education: insights from the BRAINHE project. Dyslexia, 15(1), 23-41. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.383.

Gurbuz, E., Hanley, M. & Riby, D. M. (2019). University students with autism: the social and academic experiences of university in the UK. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 617-631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3741-4.

King, L. (2018). Link lecturers’ views on supporting student nurses who have a learning difficulty in clinical placement. British Journal of Nursing, 27(3), 141-145. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2018.27.3.141

North East Autism Society. (2023). Autistic students most likely to drop out of university: investigation. https://www.ne-as.org.uk/news/autistic-students-most-likely-to-drop-out-of-university-investigation

Young et al. (2021). Failure of healthcare provision for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United Kingdom: a consensus statement. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, Article 649399. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.649399